This article originally published on Oct. 27, 2021.

“I don’t think anyone expects to go into nursing during a pandemic,” said intensive care nurse Sukdeep “Deep” Uppal, who passed his state boards and joined the ICU team full time at Clovis Community Medical Center at the end of August 2021.

Until recently, Uppal had only known what it’s like to be a nurse while wearing a tightly fit N95 respirator mask, goggles and gloves for an entire shift. Uppal began his career doing clinical rotations as a California State University, Fresno, student nurse after the COVID-19 pandemic began, later becoming an extern at Clovis Community through the end of 2020.

“Especially in the early days of the pandemic, there [were] new precautions and standards that were being updated almost daily,” Uppal said of his hospital training. “It can be a little overwhelming, but the staff here is very welcoming and supportive. They want to make sure you are comfortable and competent. Nursing is a huge learning curve, and I was surprised by that. But it helps a lot to be surrounded by a lot of great people helping you.”

Uppal said he was more than grateful for the chance at hands-on learning in the hospital environment, especially since many places eliminated or reduced clinical experiences after the pandemic hit.

Providing clinical experiences, internships for all medical professions

In a region with severe shortages of medical professionals, Community Medical Centers is the largest provider of clinical experiences and internships for nurses, sonographers, physical therapists and respiratory care practitioners.

“We have a serious shortage of nurses in the Valley right now. A lot of people train here and then they go elsewhere in California,” said Katharine McGregor, liaison for Work-based Education Programs at Community. She points to a study done before the pandemic which projected a 35% rise in demand for nurses by 2030 and a shortfall of 6,000 to 10,000 RNs to meet that demand in the Central San Joaquin Valley.

Janine Spencer, RN, who coordinates the nursing program and teaches at Fresno State, said Community has a long history of providing the critical experiences students need before they take their state nursing board exams. “When I was a student 40-some years ago, I went to Community hospitals for my clinical rotations,” she said.

“Your hospital system’s support for preceptors is important and you provide them the time to mentor students,” Spencer added. “I have so much respect and regard for [Community’s] preceptors. We could not have our class without them, and 99% of the time our students rave about their preceptors and how nurturing and supportive they are.”

According to Spencer, in the fall when Fresno State takes transfer requests for the nursing program, it gets 400 applicants for 60 openings. Nearly three times as many apply in the spring when nursing program spots are reserved for those already at Fresno State.

“[Nursing students] come here because Community has a Level I Trauma Center and we cover a huge distance for really critically ill and traumatic injuries, and it really highlights the significance of how good the nurses are that local schools push out,” Uppal said of fellow students who transferred in from southern California or the Bay Area.

Last year, Community’s hospitals and clinics trained 2,089 nursing students, like Uppal. Experienced mentor nurses, or preceptors, provided nearly 145,000 hours of supervision and teaching at a cost of $1.16 million for the hospital system. Additionally, Community Health System provided $231 million in uncompensated care, medical education, outreach and patient support services in the Valley — about 12% of the hospital system’s operating expenses. California requires hospitals to invest in the people and communities they serve as part of their nonprofit designation and to report it publicly in an annual Community Benefit Report.

Personal encounters motivated students to become nurses

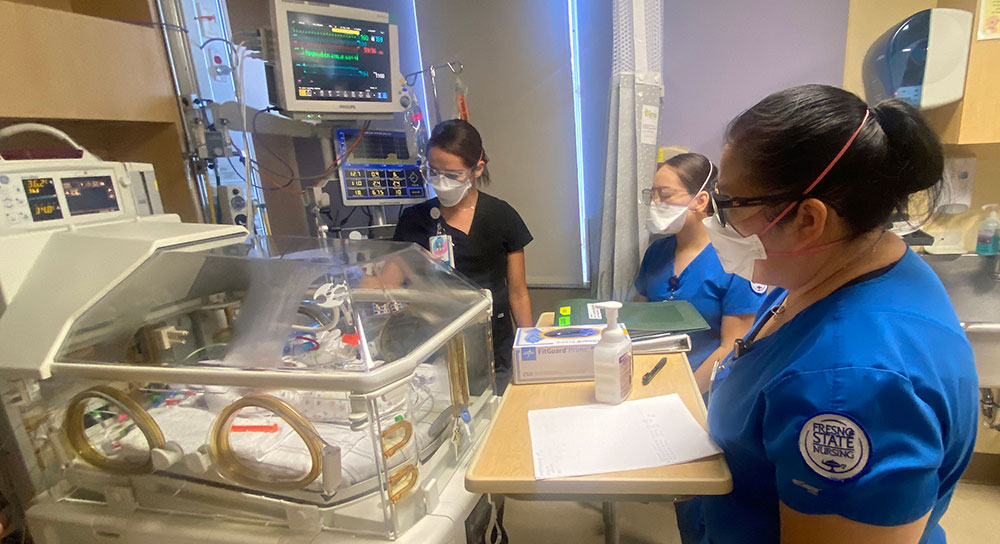

Ayde Mendoza is shadowing the nurse preceptor who took care of her when she was born prematurely at Community Regional Medical Center a little more than two decades ago.

“I knew I wanted to become a nurse early on,” Mendoza said. “When I was a child, my family and I were in a car accident and we had to go to the ER. That’s when I first realized what a nurse was, and I wanted to do something similar … When my mom told me that I was a NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) baby and how amazing the nurses were and I wanted to do the same and pass that on.”

Austin Salazar left her 12-year career with the IRS to become a nurse after her own experience with Community Regional’s NICU nurses. “I had three babies that were premature and two of them were here,” said the mother of five, who is externing with Mendoza at Community Regional’s Level 3 NICU. An externship is a program that college students embark on to supplement work experience during their educational pursuits.

Salazar’s now-teenage daughter spent 100 days in the downtown Fresno NICU after being born at 25 weeks’ gestation. She weighed just 1 lbs. 13 oz. and her dad’s wedding ring could fit around her wrist. Her third daughter spent just over a week in the same NICU after being born at 34 weeks.

Salazar’s now-teenage daughter spent 100 days in the downtown Fresno NICU after being born at 25 weeks’ gestation. She weighed just 1 lbs. 13 oz. and her dad’s wedding ring could fit around her wrist. Her third daughter spent just over a week in the same NICU after being born at 34 weeks.

“Being in the NICU is really eye-opening,” Salazar said of her experience. “Your babies are struggling on a daily basis, sometimes hourly. It’s very hard to see that as a mom, but watching the nurses take care of my kids was amazing. The nurses really helped support us as a family while we were here and made sure we were involved in our daughter’s care.”

It was Salazar’s firsthand experience that inspired her to explore nursing as a career path.

“Watching the nurses in the NICU was really inspiring and I really wanted to pay that forward,” Salazar said.“I’d like to eventually work with the community and help the community be more health literate, explaining to my patients not just what to expect but why we are doing things a certain way.”

Both Salazar and Uppal said they’re excited to work with immigrant communities as nurses and help bridge gaps in understanding for their patients.

While growing up in Madera, Uppal went to clinic visits with his immigrant parents and witnessed that confusion firsthand. “My mom and dad speak English fairly well, but sometimes they miss things. I think it’s important with language barriers that we gauge the patient’s understanding when you are going over a diagnosis or a new medication … It’s a passion of mine to educate and advocate for people from all walks of life.”

Training through pandemic required new precautions

Neither Uppal nor the NICU externs hesitated about doing clinical rotations in hospitals impacted with COVID-19 patients. Instead they worried they wouldn’t get the chance for hands-on learning.

“Going through nursing school during a pandemic is challenging. Everything is virtual and so many opportunities were limited,” said Mendoza. She was concerned that there would be so much demand for the few available externship spots that she wouldn’t get one of the paid training opportunities. “I’m very grateful that even [during a] pandemic, Community is willing to work with us and give us the training we need.”

Community, along with other hospitals, shut down student access for the first three months after COVID-19 cases showed up in the Valley. “But we got up and running again before a lot of other hospitals,” said McGregor. “We made sure all our students had mask fit testing for N95 respirators and that they all had goggles. And we did a lot of tailoring to make sure students would be going where they would be safest, but where they would still get the most experience.”

Community, along with other hospitals, shut down student access for the first three months after COVID-19 cases showed up in the Valley. “But we got up and running again before a lot of other hospitals,” said McGregor. “We made sure all our students had mask fit testing for N95 respirators and that they all had goggles. And we did a lot of tailoring to make sure students would be going where they would be safest, but where they would still get the most experience.”

Nursing students come primarily from seven Valley universities and colleges for 8- to 18-week rotations working from 5 to 12 hours a shift. They go through the same orientation process that employees do, explained McGregor. “They do online learning just like an employee on HIPAA, bloodborne pathogens, proper attire and all that. And just like an employee, they go through background checks and immunizations and we track their COVID vaccinations closely.”

McGregor added, “I think these students are some of the most prepared new nurses you’ll find in the Central Valley. I had student nurses care for me when I was in the hospital here a few years ago. A student came in and asked if she could put in my IV. She was kind and courteous and professional, and I was totally at ease.”